On December 17, 1903, the Wright brothers successfully piloted the Flyer 1, an aircraft they developed, to achieve the first sustained and controlled powered flight of a heavier-than-air aircraft in human history, and they are widely regarded as the inventors of modern aircraft. Although the Wright brothers were not the first to conduct aircraft flight tests, they pioneered a flight control system that allowed fixed-wing aircraft to fly in a controlled manner, thus laying the foundation for the practical application of aircraft. This technology is still used in all fixed-wing aircraft today.

The Wright brothers believed that there were three flying problems that troubled aviation pioneers. The first two were wings and engines. They believed that their predecessors had already accumulated a lot of technology in these two aspects, so there were no major problems. They attributed the last point to how to control the aircraft. The death of British aviation pioneer Percy Pilzer in 1899 when he lost control during a hang glider test flight made them believe that the key to successful flight, and more importantly, to safe flight, was to have a reliable flight control system. In contrast, other pioneers of their time - famous names such as Adel, Maxim and Langley - were still obsessed with building high-horsepower engines. These people often tied themselves to aircraft with unproven control systems, took off hastily without any flying experience, and prayed that good luck would take them and their aircraft into the sky.

December 17, 1903 was a historic moment - in the biting cold wind of 43 kilometers (27 miles) per hour, the Flyer No. 1 finally took off successfully. The pilot of the first flight was Orville, who flew for 12 seconds, 36.5 meters (120 feet) and a speed of only 10.9 kilometers (6.8 miles) per hour. In the next two test flights, Wilbur flew 53 meters (175 feet) and Orville flew 61 meters (200 feet). Their flying altitude was about 3 meters (10 feet) above the ground.

In 1906, members of the European Aviation Association published articles in major publishing houses to question the Wright brothers. Some European newspapers, especially French ones, were particularly blunt, openly saying that they were "bluffeurs." Ernest Archdeacon, the founder of the French Aviation Club, was particularly disdainful of the brothers' attitude. However, in the same year, the Wright brothers lobbied the US government to buy their aircraft while applying for a patent at the USPTO.

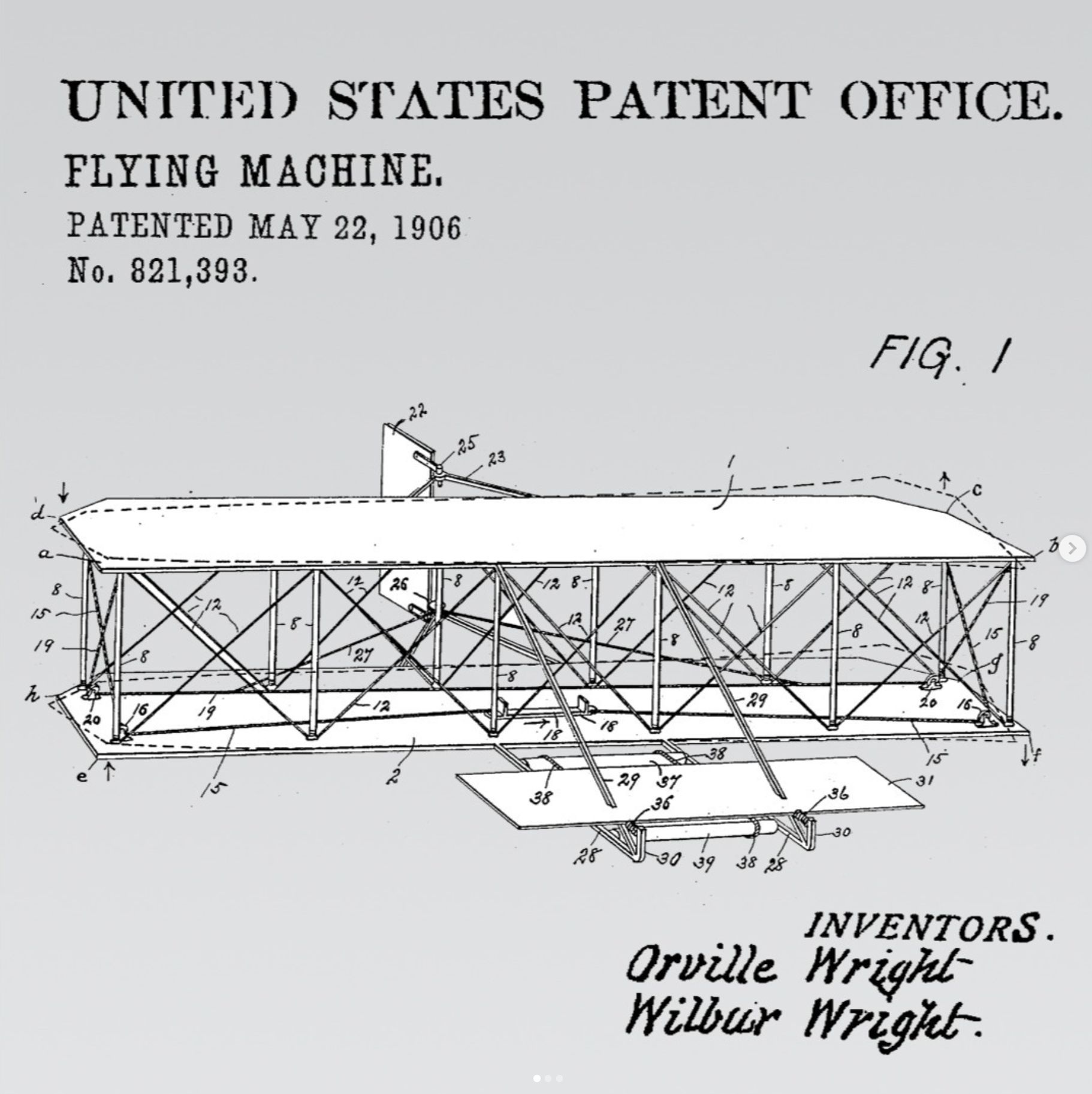

The Wright brothers had submitted a patent application for an aircraft in 1903, but it was not approved. So in 1904, they hired Harry Toulmin, a patent lawyer, to write a new patent application for them. Toulmin did not disappoint the brothers. On May 22, 1906, the Wright brothers finally obtained the "Flying Machine Patent" with US Patent No. 821,393 that they had dreamed of. The object of the patent is an unpowered aircraft, that is, their 1902 glider, but the power of the patent lies in that it claims ownership of a "new practical means of controlling aircraft", regardless of whether the aircraft is equipped with power. First, the patent describes the warping wing technology, while emphasizing the concept of "changing the wing angle in response to the airflow around the wing tip", and explicitly states that "any technology that controls the left and right roll of the fuselage by changing the outer contour of the wing" falls within the scope of the patent. The patent then describes the steerable vertical tail rudder and how it can be used to innovatively “coordinate steering” the aircraft, thereby avoiding the dangerous adverse yaw that had plagued them on their 1901 glider. Finally, the patent describes the front elevator and how it can be used to control the pitch of the aircraft.

To circumvent the patent, other aviation pioneers designed ailerons to simulate the roll control described in the patent and demonstrated in public flights by the Wright brothers. On July 4, 1908, Curtiss flew his Scarab for a historic 1 km flight, winning the Scientific American Cup. But a few days later, he was warned by the Wright brothers that he had violated their patent and was not allowed to fly or sell any aircraft equipped with ailerons. Curtiss not only refused to pay the patent license fee, but also sold an aircraft equipped with ailerons to the New York Aeronautical Society in 1909. The Wright brothers then sued Curtiss, kicking off a legal dispute that lasted for several years. In addition to Curtiss, the two brothers also sued some foreign aviation industry players, including French aviation leader Louis Bourhan. Curtis and others teased at the time: "If anyone jumps into the air and waves his arms, the Wright brothers will sue him in court." At the same time, European companies that bought the Wright brothers' patents followed them to sue other aircraft manufacturers in their own countries, but these lawsuits were only partially successful. Although the verdict in France tended to support the Wright brothers, the defendants repeatedly entangled in legal channels until the patent expired in 1917. In Germany, a court ruled that the Wright brothers' patent was invalid based on the contents of Wilbur's conversation in 1901 and Octave Chanute's conversation in 1903 that were disclosed at the time. In the United States, the Wright brothers reached an agreement with the American Aero Club to authorize flight performances approved by the club and not to sue pilots participating in the performances. In return, the organizers of activities approved by the club must pay the relevant fees to the Wright brothers.

In February 1913, the Wright brothers won the original lawsuit against Curtiss, and the court ruled that the Wright brothers' patent also applied to ailerons, and Curtiss' company immediately appealed. In 1914, the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the decision in favor of the Wright brothers, and Curtiss continued to use legal strategies to avoid punishment. The Wright brothers were satisfied with the result of the verdict, and because they were dissatisfied with their company's executives, they did not push for further legal action to ensure a monopoly on production. In fact, he had long planned to sell the company and finally put it into action in 1915, but the company continued to pursue endless litigation after the sale. In 1917, the First World War was in full swing, but these patent lawsuits had caused the US military to have no domestic aircraft available, and the US government, which was under great pressure, finally intervened. Led by the government, the Aircraft Manufacturers Association was established. With the approval of the US government, the association coordinated the major aircraft manufacturers in the United States during the war to build a patent pool. Member companies only need to pay a comprehensive fee to use any patent in this aviation patent pool, including the new and old patents of the Wright brothers. At the same time, all aviation patent lawsuits were automatically withdrawn, and the patent tax was limited to one percent. In this way, all aviation companies began to trade inventions and concepts freely. Wright-Martin Company (formerly Wright Company) and Curtiss Company also paid each other $2 million by exchanging patent licenses. Although the court's side issues caused the lawsuit to continue until 1920, the long-standing lawsuit between the Wright brothers and Curtiss finally came to an end. Ironically, Wright Aviation Company (formerly Wright-Martin) and Curtiss Company eventually merged in 1929 to become today's Curtiss-Wright Company. The successors of these two companies full of grievances are still contributing their high-tech parts to the aviation industry.

联系咨询

| Get exact prices For the country / regionE-mail: mail@yezhimaip.com |